Nikki Harris

Editor

Explore the past through music and who knows what you’ll discover. Maybe a bridge to the present.

A song written by Carly Simon in 1975, “Playing Possum,” has enchanted me since listening to it during the isolation of the pandemic. Two questions kept returning as I played it over and over.

Is this a song about the political times in which Simon was living, or is it a song about her own relationships and emotions?

Even closer to home, how is it that a song written decades in the past could sound so contemporary and relevant to us and to me? It is as though Simon was trying to capture the feelings so many people have been having during years of upheaval over Donald Trump, over racial discrimination, over the Covid lockdowns.

On the first question, as I clicked around, it became clear that the answer was both. During this period of Simon’s life, personal commitments and political ones became interwoven.

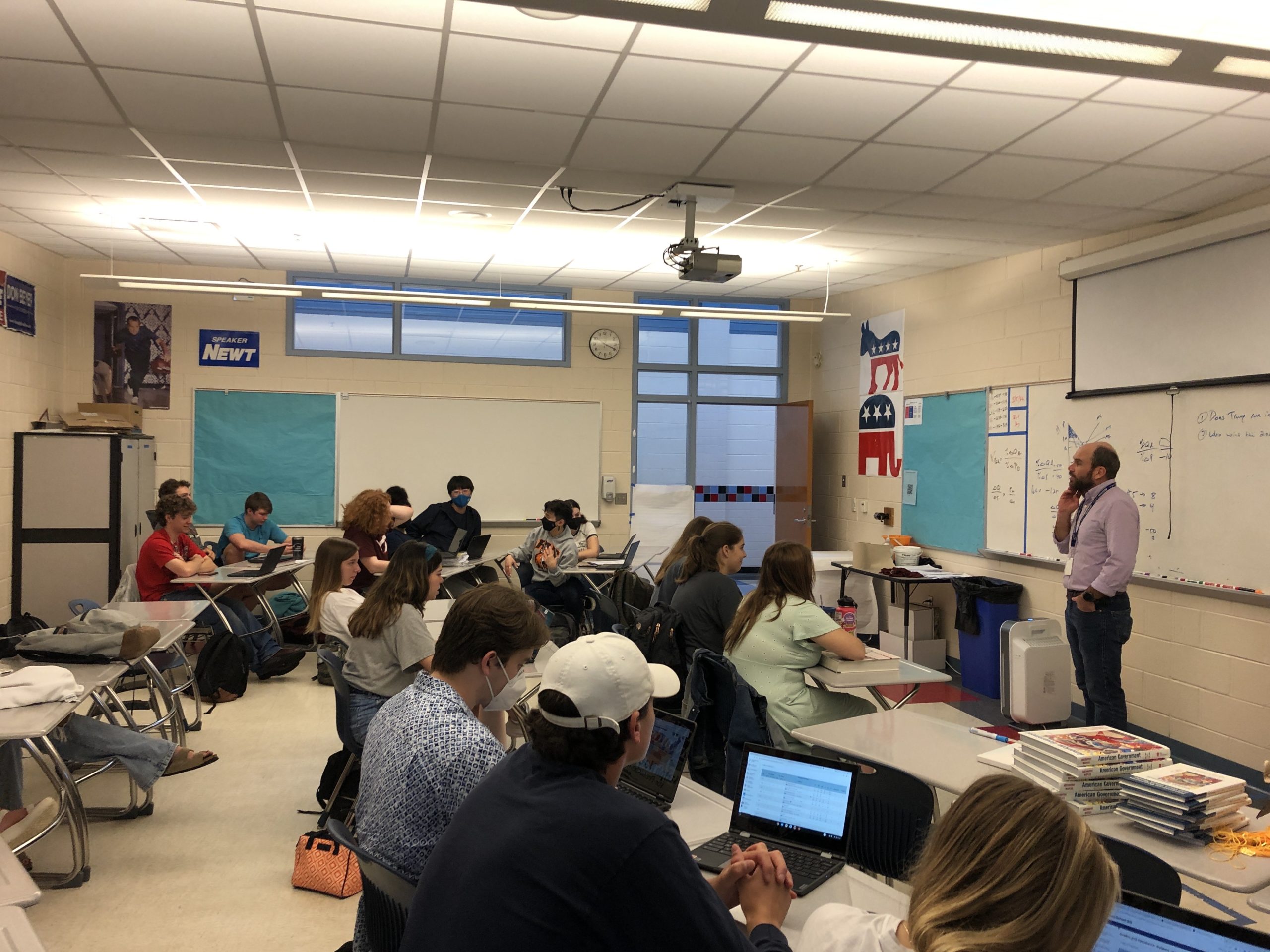

That may sound familiar to people at our school. Seniors will graduate this year from a place that has a different name—thanks to a long-overdue recognition that the old name honored someone with a racist past—and having spent more than a year of our time not with each other on campus but in our own rooms joining class from a computer. For us, the outside events of the world merged with our personal experience in more ways than we could have ever expected two years ago.

“Playing Possum,” from an album of the same name, is a song about exhaustion. Simon writes about her relationship with a man when both were deeply engaged in protest and trying to change the world.

“We lived up in Cambridge

And browsed in the hippest newsstands

Then we started our own newspaper

Gave the truth about Uncle Sam

We loved to be so radical

But like a ragged love affair

Some became disenchanted

And some of us just got scared.”

To “play possum” is to pretend to be dead to protect one’s self by withdrawing and avoiding the attention of potential predators. By the time she is writing the song, the social and political activism of the 1960s and early ’70s has passed. Her relationship with the man is over. And they’ve both withdrawn from political concerns and are trying to find peace in quiet lives.

Yet she feels pangs of guilt about this. She addresses her former lover, and by implication herself:

“And you live an easy life

But are you finally satisfied

Is it what you were lookin’ for

Or does it sneak up on you

That there might be something more.”

Simon was not alone in writing about how the political gives way to the personal as people age and their idealism and passion wanes. In “Angry Young Man,” released just a year after Simon’s song, Billy Joel writes:

“I believe I’ve passed the age of consciousness and righteous rage

I found that just surviving was a noble fight

I once believed in causes too

I had my pointless point of view

And life went on no matter who was wrong or right.”

The United States is in a period of turmoil of the sort that has not been seen since the 1960s. We will be leaving Alexandria City High School at a time when political activism and “righteous rage” is urgently needed to address the climate crisis and massive inequalities.

These crises remain as urgent as they were during the turbulence of Trump’s presidency; we can’t be lulled into complacency now. We can correct for the sanctimonious displays of virtue many of us (myself and Joel included) project as politically awakened young people without letting go of our values and concerns.

The lesson I take from “Playing Possum” is not that activism is futile. It is to remember that we have gone through similar cycles in our history, and inevitably there will be moments when we become tired and need to turn inward. Not doing so invites hopeless apathy, as Jackson Browne sang about on his 1972 hit, “Doctor My Eyes.” Describing how his constant, deliberate exposure to the worst of the world’s realities made him depressed, rather than stoical in the way he’d aspired to be, he writes:

“Doctor, my eyes have seen the years

And the slow parade of fears without crying

Now I want to understand

I have done all that I could

To see the evil and the good without hiding

You must help me if you can

Doctor, my eyes

Tell me what is wrong

Was I unwise to leave them open for so long?”

Anyone who spends time online, even on less political forums like Instagram, is unlikely on any given day not to come across horrifying photos of something like a climate-related natural disaster taking place, or starving refugees seeking shelter. These photos that seek to shock and bring attention to the issue at hand can, over time, make us feel detachment rather than urgency. And it is difficult to solve the problems we wish to solve if we are not at an emotional distance from the disasters we are constantly reminded of.

More important than how we feel is our labor to bring change. Empathy is a painful emotion to maintain and changes no circumstances on its own. Taking political action while liberating yourself from constant guilt, rage, fear, and sorrow that comes from observing the world in pain is possible. It is also in line with utilitarian philosophy that one should strive to minimize the pain and suffering of humans and animals, a group from which oneself is not excluded. So try going vegetarian without forcing yourself to watch a video of cows getting killed in slaughterhouses. Do some canvassing without thinking about how slim the Democratic majority in Congress is.

Of course, there are ways to rest without becoming “disenchanted” and settling for “an easy life.” As Simon, who is still an admired artist at age 76, tells us, we should never forget that there “might be something more.”