Critics of the project are demanding the city reevalute the effects of the project before it is implemented.

Mena Spencer, Nikki Harris, Hunter Langley

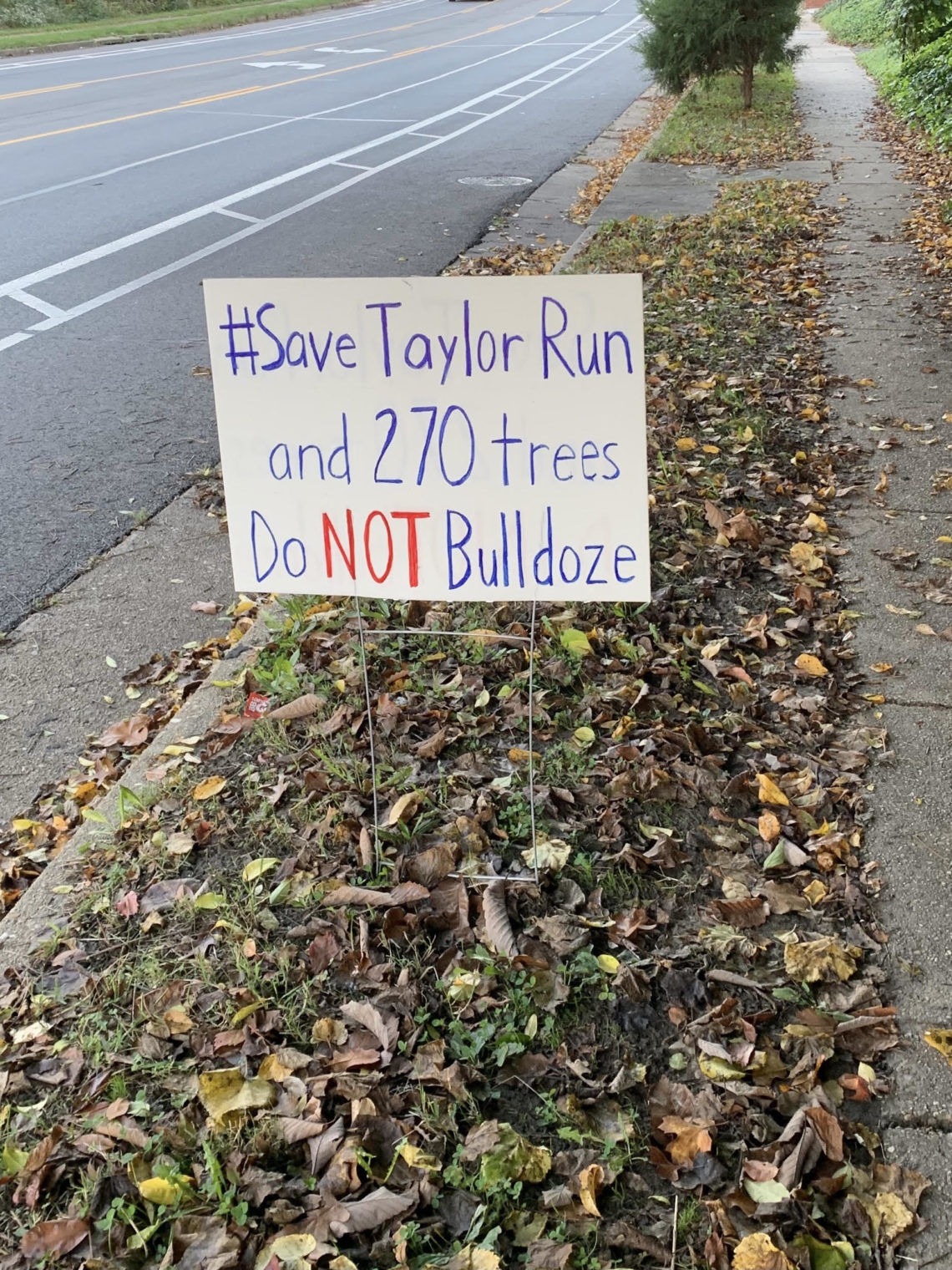

Ever since Alexandria announced a planned restoration to Taylor Run Park earlier this year, residents have been quick to voice their opinions on the matter. “Save Taylor Run” signs have popped up on virtually every other street in the areas nearby, and Alexandria residents have assembled opposition to the implementation of the current plan.

The proposed Taylor Run Restoration, which is set to be implemented around the fall of next year and will take about a year to complete, would raise the stream bed that sits below Taylor Run and–if implemented–269 trees would be removed, 208 of which are live and the remaining 61 dead.

The city website says it would replant about 2,280 trees at completion, a target Mayor Justin Wilson said would probably be the “largest tree-planting effort in the city’s history.”

But Lexye Hearding, an AP Environmental Science teacher at T.C. Williams , said that the new trees would not provide the same substantial soil stabilization, shade canopy and habitat for animals as they would be smaller and not have the centuries-old ages of the trees in place.

The City Council is arguing that the reduction of the amount of pollutants the restoration would bring beneficial for Alexandria’s long-term environmental health. It would reduce erosion, removing invasive non-native species, they say.

Wilson cited in his defense of the project the city’s obligation to the Federal Clean Water Act, which aims to protect US waters from pollution, and the requirements it must meet to comply, such as reducing the sediment and phosphorus runoff that goes into the Chesapeake Bay.

“One of the strategies that the city has undertaken over the last couple of years has been working on properties we already own: public properties. So we are..doing what’s called ‘natural stream restoration,’ where…we take public properties that contribute to runoff and we…re-naturalize them, [and] restore them back to their natural state, so that they can hold water longer,” Wilson said.

This way, “they can prevent pollutants and runoff from getting into the Chesapeake Bay,” he said. “So that’s what we are doing at Taylor Run.”

Some critics, however, don’t yet buy the idea that the pollution reduction would compensate for the potential damage done. “I am not sure that pollution reduction will be substantial given that our classroom tests have shown low levels of pollution and a variety of pollution sensitive species in the creek,” said Hearding.

Hearding said that Taylor Run houses a rare acid-seepage bog that will likely be flooded and “will lead to the loss of specially adapted ferns and rare plants in the area” if the City Council moves ahead on the project.

Hearding also voiced a concern about the impact of construction on the trees. “The plan calls for heavy construction equipment to move down the trail from the field on King St. next to Chinquapin center towards the main construction site at the rear of the community gardens at the far corner of the circle. This equipment will run over the roots of trees that are not slated for removal and possibly kill them as well,” she said.

And although the city plans to replant many native trees after the project is complete, Hearding said, “small trees do not always survive and certainly do not provide the same shade and soil stabilization as mature trees.”

The project is estimated to cost the city $4.5 million dollars, including a 2.5 million dollar grant awarded by the state of Virginia to help reduce pollution pouring into the Chesapeake Bay.

Some in the community are outraged by this. Environmental Coalition of Alexandria (ECA) member Peter Rizkallah said, “…many taxpayer dollars will be spent on the project instead of focusing these funds on things like public health and covid relief.”

The ECA and others in opposition to the project are not so much demanding a cancellation of the project as much as a reevaluation of it, specifically by fluvial geomorphologist John Field.

“The stream restoration assessments have been mostly done by computer and have not been investigated as much in person,” Rizkallah said.

One Alexandria resident, Russell Bailey, who has given tours of Taylor Run with the ECA to upward of 125 people, said the first question, “is whether you do the project at all,” but another possibility, he said, is an attempt to slow down the water flow of Taylor Run’s underground stream in high-water events if the city goes forward with implementation by, for instance, building a tank that gathers water during a storm and releasing it into the stream afterward.

“Basically we’re asking for an actual water monitoring of the water that flows out of the streams. What they did is apply an algorithm to the stream to get the best estimates. We’re saying that may not be an appropriate practice because of the unusual natural features we have at Taylor Run,” Bailey said.

Alexandria Natural Resource Manager Rod Simmons is bothered by the potential effects of the restoration as he has identified 24 native rare plant species that would be harmed by the restoration of Taylor Run, although the Alexandria City Council says it plans to replant over 30 native species in their place.

Timothy Anderson, an Earth Science and AP Biology teacher at T.C., said that he “immediately felt that it was a valuable resource that we might really endanger.”

Linda Holland, an Alexandria resident who took the ECA tour and opposes the project, said, “I don’t plan to chain myself to a tree in front of a bulldozer but the thought did cross my mind.”