The Alexandria Health Department Director said in an interview that his department holds the influence to stop distribution of a vaccine if it is skeptical of the vaccine’s safety.

Nikki Harris

Nikki Harris spoke with Dr. Stephen Haering, head of the Alexandria Health Department (AHD), on Saturday about the circumstances Alexandria could reopen schools under, vaccine politics and distribution, the AHD’s relationship with the CDC and more. Alexandria had 3,804 confirmed cases and 69 COVID-related deaths the day this interview took place. As of publication, Alexandria has 3,859 cases and, still, 69 COVID-related deaths. This conversation has been lightly edited for brevity and clarity.

Harris: I wanted to start with the possibility of schools reopening. There was an ALXNow article that said ACPS is considering sending elementary school kids back to in-person learning in a phased reopening, so can you talk about what circumstances Alexandria would do that under?

Haering: Well, ACPS, would do that under their situation. The Health Department doesn’t make the determination; we give advice and recommendations about how to hold things as safely as possible. Now the Virginia Department of Health (VDH) made a dashboard that helps schools follow the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) related to schools reopening. The CDC guidance is available online: it’s called the Indicators for Dynamic School Decision-Making. And what that does is provide all the indicators and metrics the CDC is recommending for school districts to follow. Some of those metrics the school system has under their control, and some of them they don’t, like the positivity rate in the past 14 days. The school itself can help control that, but they can’t control it through the whole community. But the metrics the school can control are the implementation of mitigation strategies, like whether they are having a consistent and correct use of masks.

Harris: What is the AHD specifically advising to ACPS, because the CDC can’t advise every individual school district in the country?

Haering: We are recommending the same thing: that there be a setup so that masks are used consistently and correctly, that there is social distancing of six feet between people, that there is hand hygiene, that there is cleaning and disinfecting going on and that there is a system so that this immediate notification between the schools and the AHD when there is a case.

Harris: But, are there positivity metrics that Alexandria would need to meet for it to be safe to go back, even for elementary schools only?

Haering: Well, we don’t use the word safe as much as we use different categories of risk. So there are positivity rates that would be considered the lowest risk, then it goes from lowest to lower to moderate to higher and highest risk. So the challenge with positivity rates is that it depends on whether a community does a lot of testing that is not efficient. So you can open up really large testing events for a lot of people who are not symptomatic at all, right? And you get a lot of negatives, and that would drive down positivity rates.

Harris: Can you talk on the state of testing in Alexandria, and how that relates to schools reopening?

Haering: Alexandria has the second highest rate of testing per capita in Northern Virginia of the five jurisdictions. Only Prince William County has a higher rate of testing than Alexandria’s. What we do is we have really enabled the private practices test; we have given them personal protective equipment (PPE) and advice about testing. Then we push out the information of where people can get testing for even reduced cost, and then the other thing we do is we conduct testing with Neighborhood Health, who we have coordinated as our community health center. And we coordinate that on a weekly basis, where we do targeted community testing, targeting neighborhoods where people traditionally don’t have as high of a level of access to healthcare; where they have higher-risk living situations; where the families have jobs where there is not any paid time off; where it is overcrowded; multi-generational housing and things like that.

Harris: Alexandria’s positivity rate has recently been at a pretty stagnant five to six percent. So, is that rate low-risk enough to send elementary school kids back to school, and maybe middle and high school kids too?

Haering: You know, the thing about that is that it depends. It really depends on what the community wants, and the tolerance level for the community to accept risk. So I can’t say whether a given percentage is tolerable. Now that is something for the School Board, the school leadership and the community to decide. What I can say is that you should not reopen if you have not done the things that you have control over–in other words, requiring that people wear masks correctly, requiring social distancing, having hand sanitizer and sanitizing solution available and using it.

Harris: Back to the testing situation, how much is our positivity rate reflective of asymptomatic and unexposed people who are getting tests because they are available versus it being a reflection of the rate among people who have been exposed or experienced symptoms.

Haering: We don’t do a lot of large testing events like some states do, where, in Florida, for instance, you can just go anywhere in virtually any county and drive up and get tested. Here we do more of the targeted testing, and telling people that a) if you have symptoms you should get tested and b) if you have been in close contact with somebody who has been ill you should get tested. So, I think, it tends to be a smaller number when you’re not over-testing.

Harris: So you think five percent is an accurate reflection of the percentage of cases in Alexandria?

Haering: Well, we know the number of people who are positive is higher than the number of positive tests–that is a characteristic of epidemiology. So we have over 3,700 confirmed cases, right? But what we know when we do serology (antibody) tests is that that number is probably somewhere two to four times lower than what the actual number is.

Harris: Right, but what about the percentage of positive tests right now? Do you think that it would be lower or higher if more people were getting tested?

Haering: We know it would be higher. But when we talk about the number of people in Alexandria and the positivity rate, we are looking at two different numerators and two different denominators. The denominator in the positivity rate is just the people who have been tested. The denominator in the percentage of people in Alexandria who have gotten it is all of the population.

Harris: I have one more question about reopening schools: the mask mandate that takes effect October 1 excludes kids ages 10 and under. Most elementary school kids are younger than 10, so would they be able to wear a mask all day if they went back?

Haering: The city ordinance follows the state of Virginia’s executive order requiring kids over 10 to wear a mask, whether that is in public or outside where you can’t maintain social distance. The recommendations from public health are that kids over the age of two wear a mask. Whether that is required or not is going to be determined by the schools. We know that the more you wear a mask, the less droplets spread, and therefore the less it spreads viruses like SARS-coV-2.

Harris: So you are saying elementary school kids could wear a mask all day if ACPS decided it was low-risk enough to send them back to school?

Haering: Yeah, if they could tolerate it.

Harris: My fellow editor Hunter Langley wanted me to ask about athletics. Where is your mind on sending kids back to contact and non-contact sports?

Haering: The AHD reviewed the ACPS athletics reopening plan and that looked to be a really good plan, that we are still doing training and fitness and all of that. The thing is, the closer and longer you are to and with someone, the greater risk that you are going to transmit or have transmitted to you. There are somewhere from 10 to 70 percent who have it who are asymptomatic, so I may actually have it right now. The roundabout number is about 40 percent. So the issue is not just the sick people but the people who are infected and don’t know it. So it’s a matter of balance between, how much do we want to not do physical activity versus how much do we want to risk getting infected. And part of that risk calculation is, who do I live with? Do I have a grandpa at home? I mean, one thing we know about this is that one in 12 Alexandrians who get this have to go to the hospital.

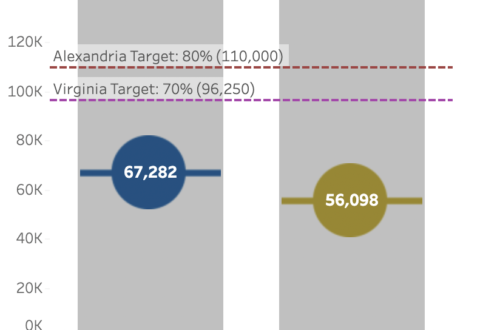

Harris: Right. I want to talk to you about vaccines now. You said in an article with LocalDVM from August that priority for vaccine distribution will be set at the national and state level, but does Alexandria play any role in getting vaccines distributed when one is approved?

Haering: Yes, the vaccines will be available, not just through the AHD, but through health care providers and through pharmacies. Like today we are conducting what we call a Flu POD (point of distribution) for the influenza vaccine. And we are doing one next Saturday, October 3, at Francis C. Hammond Middle School from 9 a.m. to 3 p.m., and we do this every year somewhere different: Cora Kelly, Patrick Hammond, etc. And what this does, is it exercises, we can practice doing these mask distributions, on a big scale. So when we get a vaccine available for the public distribution, we will operate them like we do our PODs.

Harris: Will the AHD be involved in competition with other health departments in other jurisdictions to get a vaccine distributed first?

Haering: No, what it will be is more of a cooperation, because– we work in coordination with every jurisdiction in Northern Virginia, as well as D.C. and Maryland– we will likely have our PODs open on the same day at the same time. For instance, if we were to open and the others like Fairfax and Arlington didn’t open theirs on the same day, we could interdate it from other people elsewhere, so what we will do is coordinate and open on the same days with our PODs.

Harris: And will the pharmacies that you mentioned be competing with each other for a vaccine to be distributed to their pharmacy first, or will that also be organized by the federal and state government?

Haering: I can’t say how that distribution will be coordinated. My guess is that that distribution will also be coordinated by Health and Human Services (HHS) at the federal level, so that it is even. If you look at communities across Alexandria, Virginia and the nation, there is an uneven distribution of Rite Aid, CVS, Walgreens, Harris Teeter, so it would only make sense from a broad public health standpoint to make the distribution of the vaccine even among the various pharmacies.

Harris: You also said in that article that a vaccine will be distributed first to first responders, healthcare workers and folks who are at high risk, but how will it be determined who meets the standards of “high risk” if there is a limited quantity of vaccines available?

Haering: Well, we do know in the long term there will be a lot of vaccines available in terms of how vaccine companies are ramping up. But the high risk are those who are elderly. If you look at the folks who are dying, more than 50 percent are occuring in long-term care facilities, so that would be our first focus.

Harris: Right, but what if there are only enough vaccines to distribute to some long-term care facilities in Alexandria or some elderly folks?

Haering: To talk about POD again, there are two types of POD. There is the open POD, which is open to the entire public, and then there is a closed POD. A closed POD is where we work with the facility, and we bring the vaccine to them, and then they distribute to their staff and residents themselves. So we have closed POD arrangements with long-term care facilities in Alexandria.

Harris: Let’s say there is widespread skepticism over the safety of a vaccine. What would the AHD do if you guys were also skeptical? And what would you do if you believed it was safe but the community was still dubious about it?

Haering: First, if I am skeptical of the safety of it, I will not push it out.

Harris: How much authority would you have to stop distribution in Alexandria?

Haering: I think I have considerable influence. There is the concept of control, and then there is influence. You know, I, and the other health directors and the VDH, we have principles: do no harm. And therefore if we are not satisfying the safety protocols to be met, we are not going to proceed. There are three phases of vaccine development, and the third stage is where you take about 15,000 people and you give them the vaccine and another 15,000 for the placebo. And then you see how effective that is in a real-world setting, and with 15,000 people you also see if there are side-effects of it. And the reason China and Russia are moving forward so fast is that they are skipping Phase Three of the trials. They have done Phase One, which is a few dozen people, and Phase Two, which is a few hundred. But they are skipping Phase Three and going straight to the general public, and if we see that happening here, we are just not going to proceed. The other thing is that the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has set the limit at the vaccine being at least 50 percent effective. Well, that doesn’t sound like very much, but the reality is the influenza vaccine every year is anywhere from 30 to 60 percent effective. And we know that that vaccine saves tens of thousands of lives and hospitalizations a year. So a 50 percent effective rate is actually really good for a population-level vaccine.

Harris: So let’s say the AHD does believe the vaccine is safe and effective but a large-enough group of people in Alexandria don’t want to take it for whatever reason–then what would you do?

Haering: We already are planning our communication campaigns and strategies. We will be reaching out to social influencers on social media and telling them the facts and asking them to use the messages that public health has developed, because there are a lot of anti-vaxxers and anti-maskers. And we in public health need to insist that we are not going to be bullied, that we are not going to back down from science. And if people want to make a lot of noise for whatever reason, either because they are misinformed, they don’t trust science or they are trying to make a political statement, that is fine, but that is not going to bully me into doing my job as a public health director.

Harris: How much do you expect cases to rise as it gets colder and outdoor gatherings are unfeasible?

Haering: What we know when we look at influenza is that it tends to rise in the colder months, and that is because more people spend time indoors in closer quarters, and there can be less ventilation. So we do anticipate that coronavirus cases will increase. And it’s also a matter of the fact that people are getting out more, and there is more mingling. And so I expect it to kind of come in waves. It will dip, and get worse, and then dip, and then get worse, and it will do that through 2021, well beyond a vaccine. I should tell you one more thing about vaccines. One thing they do is that they can eliminate diseases, like tetanus or measles, because tetanus vaccines are, like, 99% effective. But with influenza, you can still get the disease but it reduces the severity of the disease. Another thing a vaccine does is it can reduce the transmission from a person who is infected to the other. What we don’t know and won’t know for some time about the COVID-19 vaccine is how much it will reduce transmission from people who are infected to others. And without knowing that, that is why I am saying we are going to be working through this pandemic through 2021–it won’t be over one or two months after a vaccine.

Harris: As I said earlier, Alexandria has had a pretty steady positivity rate, so what positivity rate does the AHD consider both ideal and realistic, and how is it trying to get there?

Haering: Again, the positivity rate is driven by the number of people who are getting tested. When we look at the CDC guidance, the ideal positivity rate for lowest-risk transmission is one to three percent. And so what we are doing as a health community, is getting the message out about where to get tested, and doing case investigation and contact tracing. If we get a hold of the case within 24 hours, we make sure they have the ability to isolate for their infectious period, which means they might need rent assistance or food. Most people don’t need anything but many do. The second part is contact tracing who they were with 24 hours before they feel sick or they get tested. We contact those people and tell them to quarantine during their incubation period.

Harris: If cases start to rise again and the AHD loses the ability to do case investigations or contact tracing, would it consider another stay-at-home order?

Haering: What would happen if we did that is that it wouldn’t just be Alexandria. What happens here happens to Arlington, Fairfax, Prince William County, so if we saw cases go up, the City Council, as well as the Board of Supervisors of the other jurisdictions would petition the governor to increase the mitigation strategy. It could be, not necessarily a stay-at-home order, tightening the restrictions on a particular industry or activity where there are outbreaks in cases.

Harris: The CDC has recently been accused of being politicized–it put a memo up that said COVID-19 is airborne and then took it down, and it changed the standards one must meet to get tested. So what is the AHD’s relationship with the CDC, and how are you guys approaching messaging in conjunction with the CDC?

Haering: You know, I have a tremendous amount of respect for the CDC, and I have very principled colleagues who work there. And there is a lot of politics going on there; they are caught in between the science and the politics. So we use the information they put out, and we also look at the primary literature like the Journal of American Medical Association (JAMA), The Atlantic and lots of other sources. So with the airborne versus droplet situation, we know that this is carried by droplets, and it is probably carried somewhat by airborne transmission, but not like the type of airborne like tuberculosis and measles. And when we talk about airborne transmission, it usually means the type that gets in the heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) system. We know this virus is not getting in the HVAC system, because it is not infecting people in any given building four floors away. And that is what happened with SARS–in Hong Kong, people were sick on the third floor and other people got infected on the eighth floor. So I think as more research is done, we will see a category that is in between the traditional airborne and the droplets.

Harris: So, do you guys at the AHD contradict the CDC when it is resisting the science?

Haering: Well, I wouldn’t say they are resisting the science. The CDC has to be more cautious and have more evidence to say something, and I can’t really think of anything off the top of my head that we would be contradicting them on. It is important to remember that this is a new virus, and we are learning. Back in February and March, we and the CDC were saying not to wear a mask. And with increasing evidence of which communities in other countries were getting infections and which ones weren’t, the CDC came out April 3 and said that masks actually work. So we are always adapting to the information that the researchers come up with.

Harris: Thank you so much for making the time to talk to Theogony. Do you have any last words for our readers?

Haering: Yes, we need to all focus on the things that we can control. It is not just adapting to new behaviors like mask-wearing and social distancing, it is adapting to a new culture of safety, a new culture of compassion and concern for our neighbors. Your health depends on my health and my health depends on your health.