Bridgette Adu-Wadier

Read the original story here on PBS NewsHour Extra.

While politicians attempt to engage young adults (ages 18-29) each election season, this group has had low turnout for decades.

But we may be seeing a shift. In 2018, 36 percent of young people voted nationwide in the midterm elections – a large jump in turnout compared to the 2014 midterms, where 20 percent of 18-29-year-olds voted, according to the U.S. Census.

But will they come out again en masse in the 2020 general election? While overall youth voter turnout this primary season has disappointed some Democrats, particularly in the Bernie Sanders’ camp, younger voters participated in more voter registration drives and engaged in more political activism than in 2018, according to the Center for Information & Research on Civic Learning Engagement (CIRCLE) at Tufts University.

“There’s no doubt that young people will have an impact with the issues that they care about.”

– Abby Kiesa

“There’s no doubt that young people will have an impact with the issues that they care about,” says Abby Kiesa, director of impact at CIRCLE.

From climate change to guns and education, many young activists have made national headlines in their efforts to mobilize thousands of other young people. And it is not just the Greta Thunbergs of the world who are making big changes. Youth power political campaigns on the local, state and national levels.

“The amount that young people work on campaigns is immense,” said Kiesa. “By working on campaigns, elections, investing in leadership, investing in training young people — the time that they invest is really important.”

Youth-driven initiatives such as voter registration drives can help remedy the lack of participation by triggering habits that build over time to increase turnout, according to Kiesa.

Opportunities such as volunteering on campaigns are not just pivotal for future voters. They are also learning experiences for those who cannot vote or are not yet eligible.

Voter turnout for young people has stayed low for various reasons, according to the Center for American Progress, including insufficient civics education, a voting process that’s difficult to navigate, relocation for college and jobs as well as missed registration deadlines.

Many youth face barriers to voting, such as lack of language access, voter ID requirements and reduced early voting opportunities.

Mikaela Pozo, a T.C. Williams High School senior in Alexandria, Virginia, volunteered for a local school board member’s campaign and currently interns for the vice mayor of the city. Though she can’t vote in 2020, Pozo’s civic engagement taught her the value of voting.

“I think being able to vote is a privilege,” said Pozo. “I think the fact that I can’t vote compels me to be more politically active and encourage people to vote,” she said.

CIRCLE’s Kiesa agreed. “The more you vote, the more likely you are to do so for life.”

Pozo, along with college students, Jay Falk and Allison Criss, also participated in voter registration drives.

“I’ve always had a passion for voter registration,” said Criss, a first-time voter and a junior at Liberty University in Lynchburg, Virginia. In high school, she lobbied members of the Virginia General Assembly on education issues.

“The people we elect will end up doing their job as long as we put pressure on them. It shows the power of voices of people stepping up,” said Criss.

Falk, a sophomore at the University of Pennsylvania, registered about 450 students to vote in her senior year of high school and organized students to educate others about voting and government.

Students are seen as having less power at colleges and universities than faculty or administrators, according to Falk, adding, “Voting is a way to exercise power.”

“I will never not vote because not voting is throwing your power away.”

– Jay Falk

Along with voting barriers, civics education is still insufficient, said Falk, who had not taken a government class in years until her senior year.

“I think the one time we talked about something related to civic engagement was the [yearly] mock election at my school,” said Pozo. “I think that is so late in the game.”

Only one-quarter of high school seniors were found to be “proficient” in civics, according to 2010 results from the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), commonly called the Nation’s Report Card. Across the country, 42 states and Washington, D.C. require at least one course related to civics education, the 2018 Brown Center Report on American Education found.

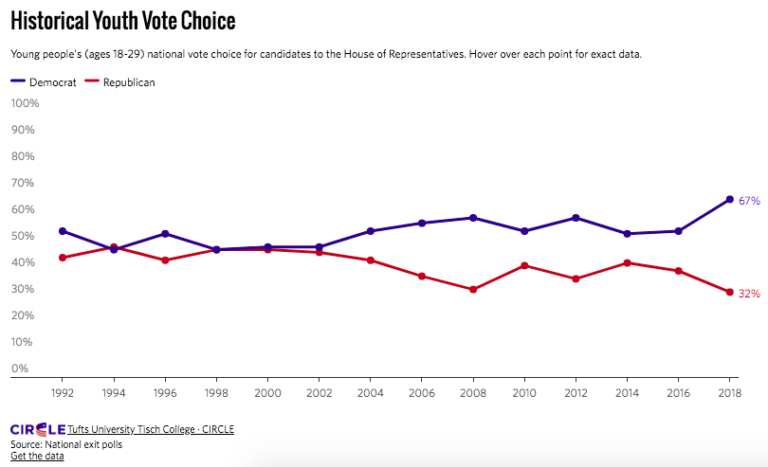

Another factor making youth less likely to vote is an ambivalent attitude towards political parties, according to CIRCLE. About 56 percent of youth identify with a political party. Independents are significantly less likely to vote. Despite historical preference for Democratic candidates, increased polarization between conservatives and liberals has turned off many young voters.

“I really want to go outside the two-party system,” said Alexis Jones, a senior at Thurgood Marshall Academy in Anacostia, D.C. “I prefer not to pick sides and I don’t agree with sectionalism. I don’t want our government to be divided based on political parties.”

Generation Z will most likely be the most diverse voting demographic, Pew Research reported. Along with this diversity comes young conservatives like Criss, who are different from older conservatives.

“A lot of young conservatives are more open to discussions than the middle-aged crowd,” said Criss. Young conservatives tend to be more moderate and concerned about the environment, health care and some social issues.

Falk, Pozo and Criss all have a vast array of issues as their priority this election season, such as military funding, immigration, education, health care, affordable housing and the climate change.

“How young people vote and who they vote for can be important regardless of turnout rate,” said Kiesa.

Voting is one way young people can demonstrate their collective power, Falk said, adding that she’s excited to vote. “I’m going to cast my vote while I’m thousands of miles away. I will never not vote because not voting is throwing your power away.”