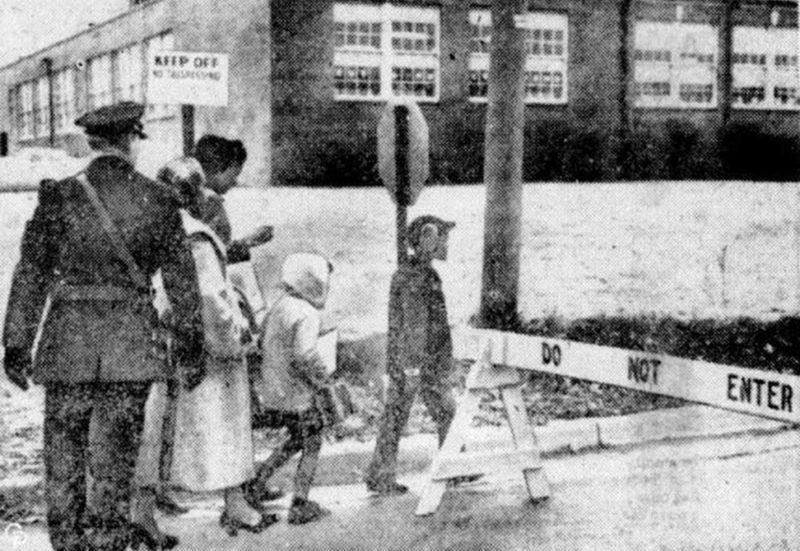

On a damp grey morning at 8:15 a.m. on February 10, 1959 — exactly 60 years ago this week — two African-American school children from Lyles-Crouch School walked across a line of 58 police officers to become the first black students at Theodore Ficklin School — until that day an all-white elementary school. On the other side of town, three other African-American children — who had previously been bussed across town each morning to attend all-black Lyles-Crouch — walked into the all-white William Ramsay School. Their actions were the start of a long, slow process to desegregate Alexandria City Public Schools that took another 14 years to complete.

Those African-American children almost immediately disappeared into the school system and only a handful of the nine students have spoken about their experiences that day. In this article — the third in a series that looks at the impact of Brown v. Board of Education on Alexandria in the 65th anniversary year of that decision — we track down a few of these former students to learn what happened that day and delve into the issues that surrounded elementary desegregation.

Kathryn Turner was 12 at the time. Her sister Sandra was in second grade and her brother Gerald was in first grade when all three were reluctantly permitted by the superintendent and school board to take classes at William Ramsay School.

Their family had moved from Chicago to the rural all-black community near the current Landmark Mall nine years earlier to live on her grandparents’ farm. Although they had no running water and only an outhouse, her mother had a masters degree, believed in a good education, and her parents were active in the NAACP and wanted the children to attend their neighborhood school. None of the children remember their parents telling them the reasons they had opted to join the NAACP lawsuit against Virginia school systems resisting integration, but they did know that their parents had never lived anywhere where education was segregated before.

“They were deeply committed to education and found it uncomfortable. My parents always had a very positive attitude and believed everyone is born equal — no less, no more — that we are all born as children of God and that everyone is accepted and has a right to be treated with respect. No one can take that away from you,” Kathryn said.

“I don’t remember conversations about the fact that we were going to do something different. I don’t have memories from those days. I don’t think I found it particularly hostile, but I do know that nobody came home with me,” she added.

Kathryn and her siblings were exactly the type of children that the NAACP was looking for to support their civil rights lawsuit. Kathryn went on to graduate from D.C. Public Schools, attend Howard University, majoring in chemistry with a minor in applied physics and math, went into software development in the 1960s and started her own tech company in 1985 that fulfills contracts for the Department of Defense.

One of the requirements put in place by the school board and superintendent just a few weeks earlier said that any African-American children requesting a transfer should be of above average intelligence.

On the other side of town, James and Margaret Lomax also matched the NAACP’s need. They were both bright children. Margaret (then 6) went on to become valedictorian and her brother James (then 8) achieved all A’s and B’s throughout his education. Their mother Ella Lomax just wanted her children to have a safer and shorter walk to school. The white-only Theodore Ficklin School was just a block from their house, while Charles Houston — the school for African-Americans — was further. Their father had served in the U.S. Army, fighting for democracy, and she felt it right her children should be entitled to their share of democracy, too.

The first African-American students to break the racial barrier in Alexandria did not have an easy time of it. Some students were pelted with spitballs. They were tripped in hallways. Books were knocked out of their hands. Some received undeservedly low grades.

“I don’t recall being frightened going to our new school but remember a crowd of people and not getting much of a warm welcome in the classroom. My overwhelming memory from that time is of isolation, being marginalized and not being fully welcomed or accepted. As an elementary student, I had to adapt to the isolation and was determined to succeed. I was a good student and I worked hard,” said Kathryn’s sister Sandra Bond, who remembers trying to eat lunch with her brother and sitting next to him on the bus.

“They suffered the stares of classmates and the racial slurs shouted from passing cars,” according to former Alexandria teacher Mable Lyles.

There were other serious consequences.

Originally, 14 children had been selected for the civil rights case, but not all ended up as part of the final lawsuit. Among them were Pearl and Theodosia Hundley, whose mother Blois wanted them to learn a foreign language and felt that Theodore Ficklin offered better educational opportunities. She was at a PTA meeting at the all-black Parker-Gray School when parents were asked if anyone would be interested in having their children attend the white schools and would be willing to join the NAACP lawsuit against Virginia school systems resisting integration.

As a result of her support of the lawsuit, their mother — a cook at Lyles-Crouch — was fired by Superintendent Thomas Chambliss (T.C.) Williams. Even though she was later reinstated, she pulled her children out of the school system and moved into Washington, D.C. Consequently, Pearl and Theodosia were never part of the lawsuit.

“We couldn’t very well continue to employ her after such a slap in the face. If we had continued, it would have been condoning her action. Her race had nothing to do with it. If she had been green it would have been the same thing,” T.C. Williams told the school board.

But despite this brave action, it took another 12 years for the next steps to be taken to fully integrate the elementary schools. By 1971, many were still segregated due to the location of schools in racially segregated neighborhoods.

In addition to huge disparities in elementary enrollment in 1971, there were also racial disparities among staff. In 1959, Kathryn Turner had not found a single teacher who looked like her at William Ramsay — although she fondly remembers her white biology teacher Ms. Gates, who set high expectations for her and helped her fall in love with science.

The teachers at Francis C. Hammond were also all white, and the community complained that the opening of the new Jefferson-Houston school in the late 1960s was, in reality, a continuation of the former virtually all African-American school, except by a different name. Even though new elementary schools were opening in the late 1960s and early 1970s, nothing really changed. The location of new schools ensured segregation continued in practice.

So Why Did Elementary Schools Take a Back Seat in 1971?

The new superintendent, John C. Albohm, believed that a wholesale integration of elementary schools at a time when there was already significant racial turmoil at the high school level, would result in white families pulling their children out of schools and moving out of the area. Albohm was concerned about disturbing long-established patterns of race at the elementary level and resisted changing the neighborhoods, which created the segregated elementary schools. He felt full-scale desegregation would have been too much for the city all at once.

“There is a caution on our part, and maybe a caution on the part of the school board and the community, because of the existing power structure and federal injunction in the Sando suit,” Albohm said, referencing the lawsuit against the integration of the high school.

The school board sought to dodge the issue, claiming that three new members had recently joined and therefore could not make such an important decision. But in avoiding elementary desegregation, 12 years after the initial action, Albohm, the administration and the board were all preserving the vestiges of Alexandria’s old segregated school system.

1972 and the Dispute Over Busing

Renewed focus on the elementary schools began in 1972 when the federal government’s Civil Rights Director J. Stanley Pottinger called Albohm to ask him about the status of elementary school desegregation. The phone call resulted in an agreement that no elementary school would have more than 50 percent black enrollment. Some were as much as 95 percent African-American. The plan to resolve this would involve busing students around the city.

The rumor that elementary schools were about to be desegregated brought crowds out to the March 1972 school board meeting opposing the change. The George Mason PTA president said 95 percent of its members were against busing and described the school as the equivalent of a church: “the center of neighborhood activities.” Albohm backed down and said he would no longer bus students across the city.

The dispute over elementary busing to try to desegregate the school caused the conservative city council, who appointed the school board members, to flex their political muscle. They replaced the liberal members who supported desegregation of the elementary schools with conservatives.

In June 1972, Chair Ferdinand T. Day — Alexandria’s first African-American school board member — stepped down and the new board was stacked with opponents of busing. Katrina Ross, the sole African-American left on the school board, resigned in protest at what she described as a reversion to the 1950s and alienation of the African-American community. She called on black Alexandrians to boycott the selection process for her replacement.

The Solution? Pairing Schools

In April 1972, Albohm presented seven integration plans to the board, including one that involved busing both white and black children to cross-town paired schools. A predominantly white school would be paired with a predominantly African-American school. Students would attend some grades at one school and other grades at the other school. The solution meant that neither white students nor African-American students bore the brunt of busing — both shared it equally.

Although racial inequities still existed, the local political forces that had initially sought to resist and then contain black and white integration within Alexandria were defeated. With this decision — 14 years after the first black student entered an all-white school — race was no longer the basis on which Alexandria organized their schools.

For Kathryn Turner, “racism is alive and well” and there are times when she still experiences it.

“That’s why I started my own business — to create an environment where everyone can have the opportunity based on their capabilities, not on their race or color. One lesson I learned though from my experience at Ramsay and Hammond in the 1950s is how to fit comfortably into any group of people. I have been able to fit into a lot of different situations in life. The more different experiences you have, the broader your mind and the more able you are to achieve things. That’s what the experience in Alexandria did for me,” she said.

Read the full interview with Kathryn Turner and Sandra Bond.

The history depicted in this post is derived in great measure from “Building the Federal School House: Localism and the American Education State,” by Douglas Reed, along with interviews of the children who changed schools in 1959.

Read other posts in this series:

- The Anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education – What Does it Mean for Alexandria?

- Brown v. Board and Football: Both a Problem and a Solution

Learn more about the history of ACPS.