When Onelio Mencho-Aguilar was 13-years-old, he left his mother and siblings to embark on a treacherous journey through rural Guatemala to the U.S. alone. His hope? That he could find a job and send money to his struggling family.

He spoke neither English nor Spanish, only Mam, a Mayan language used by just half a million people.

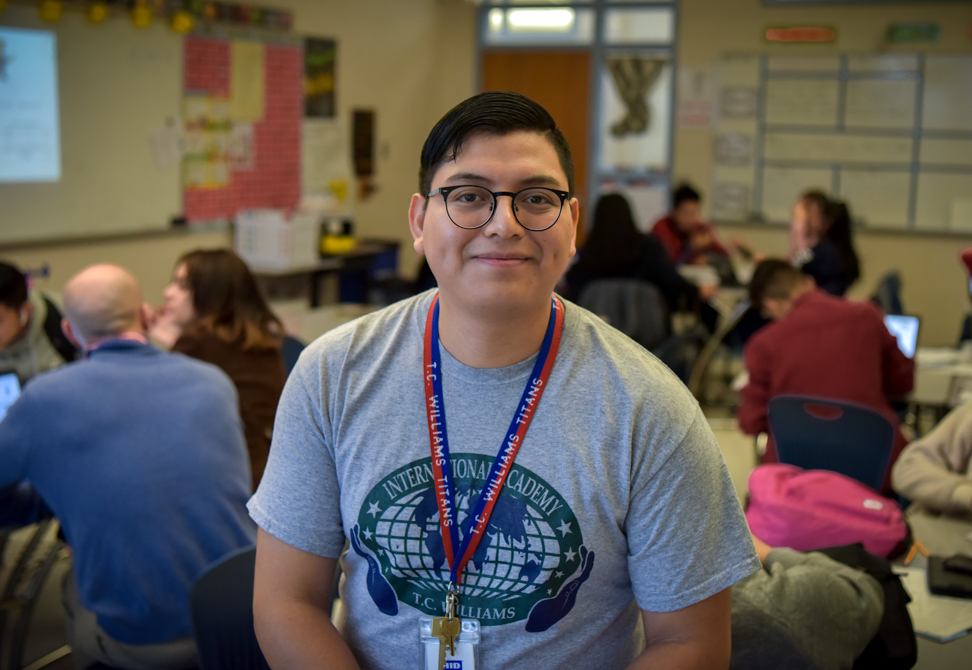

But against the odds, he found a home here in Alexandria and with the support he found, he thrived. First as a student at T.C. Williams High School and now as a teacher at the International Academy where new arrivals to the U.S. are educated and supported.

The soft-spoken 27-year-old uses his own incredible story to inspire and encourage his students.

“I share my story with students every day, especially my new students. I share a lot of things in common with them. So every single day I try to cheer them up because I know that they’re going through a lot of hardships in life. Finding that common ground with them is really helpful because I want to be that person that they can trust.”

As a child growing up in the hills of Quetzaltenango, he was all too aware of the struggle his single mother of four children faced to make ends meet.

She scraped together a living by working in corn and potato fields and weaving huipiles, traditional Mayan dresses, to sell.

One day, when he told her he planned to leave and go to the U.S. to earn money, his mother understandably said no.

But a few months later, facing unthinkable hardship, she reluctantly agreed to let her determined son take his chances.

At first, he said, the journey was exciting, one big adventure to be traveling through cities and countries as a wide-eyed teen.

Yet when he reached Mexico, things changed and the reality of what he had undertaken hit him.

“Once I started taking the train out through Mexico, I realized that I had taken a really dangerous decision. I thought about going home several times,” he said.

It took him a month to reach the desert on the Mexico/Arizona border where he paid a coyote to lead him to the U.S.

“I walked in the desert for four days, and we didn’t have enough water and food and we were lost. So that was very, very dangerous and scary for a lot of us. I remember that there were a lot of young people with us as well. I got sick, I thought I was going to die.”

Eventually, one night he saw lights in the distance. A feeling of relief poured over him as his dream of America came into view.

From Arizona he traveled to Los Angeles and got a job on a construction site but when his age was discovered, he was fired.

With no money and nowhere to stay, he wandered the city for days, frightened and alone.

He was helped by a Mexican woman who saw him crying at a bus stop. She arranged for him to travel to Virginia, where he reunited with a father he hadn’t seen for ten years.

Despite a difficult relationship, he credits his father with enrolling him at school, first in Arlington and then to Minnie Howard and later T.C. Williams.

“I remember my first day going to school and we were taken to the library and I just fell in love with the books and the smell of books. I was just surprised by the number of books in the library, too, because where I came from, we didn’t have access to even a library and so seeing that here opened my eyes.”

“I had a lot of amazing teachers, and I think that’s one of the many reasons why I succeeded was because of great teachers who really cared about me, cared about my learning, and also cared about my well-being. I had a teacher at T.C. who was the first person that noticed that I was in need and started reaching out to social workers who could help me.”

To graduate on time, Mencho-Aguilar devoted himself to his studies, enrolling in summer school and night classes.

When his father returned to Guatemala, he ended up in foster care.

Yet his academic success led to him being featured in the Washington Post nine years ago.

He went on to study at NOVA and then transferred to Marymount University, majoring in English literature, with a goal of entering law school.

But an internship at a law firm in his senior year of college put an end to any legal ambitions.

“I realized I just didn’t like anything related to law. Then an opportunity came up, and I started substituting at T.C.’s International Academy. I was a long term substitute teacher and I just fell in love with interacting with the students, learning about them and teaching them.”

“I would say there was a moment when I realized that I could actually make a positive change in this world and inspire other students.”

He is now a permanent and valuable member of the teaching staff and works alongside some of his former teachers who were so important to his own success.

His life experience has become a major asset to his career as he can relate to so many of his students who find themselves in a similar position to himself as a child.

“I am someone that looks like them, someone who speaks their language now and someone who has actually made it and was able to graduate and go to college. I think that sends them a strong message. Like my students, I still miss home sometimes. I left family and had to get used to the new culture here, learn the language.”

“Just talking about the food, the music or even the festivals that we celebrate in our countries helps, especially if they are feeling homesick. I want them to think, ‘Oh, yeah, I should motivate myself and work hard.'”

And the satisfaction from seeing his students graduate?

“One of the best feelings of my life,” he said.