One of our nation’s first experiments in public education with African Americans took place in Alexandria. Centuries later we were again at the forefront — although perhaps not in a good way — regarding the superintendent’s resistance over the desegregation of the schools.

This is the story of ACPS. It is a long, complex and messy story. It goes far deeper than the one we know from the Disney movie. Take a few minutes to read this summary. You can find the full history of ACPS on the ACPS website.

This is a work in progress, so if you have something to add, email us at news@acps.k12.va.us.

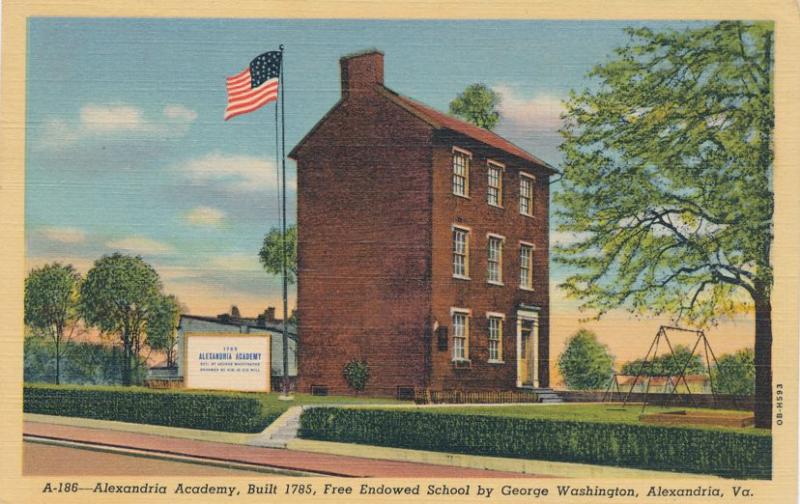

1785: The Washington Free School / Alexandria Academy

The Washington Free School — next door to the Little Theater of Alexandria — was founded in 1785 for the purpose of educating orphans and the poor.

The academy building was vacated after the War of 1812, and by the time Robert E. Lee became a student (from 1818 to 1823), a school for African American children had opened on the third floor. The school, funded in part by George Washington with a $4,000 bequest in his will, therefore educated all — albeit separately on two separate floors.

One of the enslaved students at the school, Alfred Parry, later became a teacher and by the early 1830s had opened his own night school. After an 1837 law forbade the assembly of blacks, Parry managed to open a day school, Mount Hope Academy, by hiring a white man to act as his cover. Located between Duke and Wolfe streets, Mount Hope educated free and enslaved blacks until 1843.

One of the enslaved students at the school, Alfred Parry, later became a teacher and by the early 1830s had opened his own night school. After an 1837 law forbade the assembly of blacks, Parry managed to open a day school, Mount Hope Academy, by hiring a white man to act as his cover. Located between Duke and Wolfe streets, Mount Hope educated free and enslaved blacks until 1843.

1920: Parker-Gray School

In the early 1900s the Snowden School for Boys and Hallowell School for Girls opened as public schools for black children in the City of Alexandria. In 1920, the Snowden and Hallowell schools were consolidated into the Parker-Gray School, named for John Parker, principal of the Snowden School, and Sarah Gray, principal of the Hallowell School.

The Parker-Gray School served African Americans in grades one through eight on the site of the current Charles Houston Recreation Center on Wythe Street. It had nine teachers, few school books or resources and the barest necessities. Members of the community provided chairs and basic equipment. For many years, African American students had to travel to Washington, D.C. to receive an education beyond the eighth grade.

The Parker-Gray School served African Americans in grades one through eight on the site of the current Charles Houston Recreation Center on Wythe Street. It had nine teachers, few school books or resources and the barest necessities. Members of the community provided chairs and basic equipment. For many years, African American students had to travel to Washington, D.C. to receive an education beyond the eighth grade.

By the early 1930s the school was overcrowded. A new school was established in an old silk factory at the corner of Wilkes and South Pitt streets for black children who lived south of Cameron Street. It was named Lyles-Crouch to honor Jane Crouch and Rozier D. Lyles. Mrs. Crouch was a principal at Hallowell School; Mr. Lyles taught at Snowden School and at the first Parker-Gray School.

Parker-Gray was soon overcrowded again, so classrooms and a library were added. The first students who attended Parker-Gray for grades eight through eleven graduated in 1936 as Virginia required only 11 years of public education.

When the Parker-Gray High School was built in 1950, the original Parker-Gray School was given the name of Charles Houston, after the NAACP lawyer who helped the community in their quest to have the high school built. During the desegregating years, Charles Houston Elementary School closed and the building eventually burned down. This site is now home to the Charles Houston Recreation Center.

The community realized that a separate high school building was needed. The Hopkins House Men’s Club and other groups asked the help of the NAACP. NAACP lawyers, headed by Attorney Charles Houston, conferred with city, state and federal officials. Eventually, the Parker-Gray High School was built at 1207 Madison Street. It was dedicated on May 31, 1950 and remained the high school for black students until 1965.

In the fall of 1964, all sectors of the Alexandria school system — students, faculty, and staff — were integrated. Parker-Gray High School was closed in 1965 and black students attended the city’s other high schools: George Washington High School, T.C. Williams High School, and Francis C. Hammond High School.

From 1965 until 1979, the building served as a middle school. The property was sold and a portion of the funds was used by the City of Alexandria to renovate and extend the Alexandria Black History Resource Center, now the Alexandria Black History Museum. In the early 1980s the building was demolished, but a plaque marks the location of the old school.

Before the last home football game on October 29, 1983, the stadium at T.C. Williams High School was dedicated as the Parker-Gray Memorial Stadium. The School Board’s decision to name the stadium the Parker-Gray Memorial Stadium was an acknowledgment of community pride associated with a high school that served this city well.

1959: Desegregation of Elementary Schools – The Action that Took 14 Years to Complete

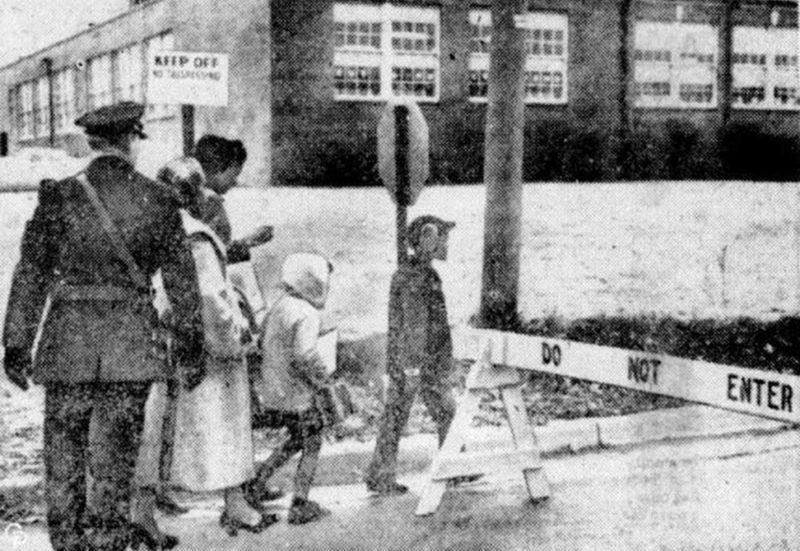

On a damp grey morning at 8:15 a.m. on February 10, 1959, three African American children who had previously been bussed across town each morning to attend all-black Lyles-Crouch walked into the all-white William Ramsay School. Their actions were the start of a long, slow process to desegregate Alexandria City Public Schools, which took another 14 years to complete.

Kathryn Turner

Those African American children almost immediately disappeared into the school system and only a handful of the nine students have spoken about their experiences that day. Kathryn Turner was 12 at the time. Her sister Sandra was in second grade when, along with their brother Gerald, they were reluctantly permitted by the superintendent and School Board to take classes at William Ramsay School.

Read the ACPS interviews with Kathryn Turner and Sandra Turner-Bond.

Although Alexandria neither led the charge to resist desegregation nor was the first to desegregate in Virginia, in many ways the story of the initial steps to desegregate has come to represent the intensity of the issues and the racial conflict that persisted long after desegregation.

Many of us know the story of Remember the Titans. But the story of the desegregation of Alexandria City Public Schools is far more intense and darker than the glamorized and sanitized story presented by Disney. While ACPS and our community celebrate our diversity today, it took federal legislation, political unrest, violent protests, and changes in the composition of Alexandria’s School Board and City Council and a new superintendent to get to what at least looked like full integration — and even then it was not fully integrated in practice. It would be twenty years after Brown v. Board of Education before a full integration plan was in place in Alexandria. Some of the issues the city faced at that time are still relevant today.

The entrenched nature of the Old Guard in both the city and the schools meant that the federal court decision ordering Alexandria City Public Schools to comply with Brown v. Board of Education in 1954 was a direct challenge to the local political situation. Alexandria’s mayor from 1952 to 1955 was Marshall J. Beverly, a cousin of U.S. Senator Harry F. Byrd, Sr. who led the statewide pro-segregation campaign known as Massive Resistance, while Alexandria State Delegate James M. Thomson was Byrd’s brother-in-law. Alongside them was Superintendent Thomas Chambliss (T.C.) Williams and a conservative School Board. The affiliation was so strong that when the city eventually complied with desegregation, it brought down the local regime.

Across Virginia, schools that desegregated voluntarily were closed down. In Alexandria, local officials strategically used these threats of state-imposed punishment and closure to argue for an indefinite delay of desegregation in the wake of Brown v. Board of Education. The court decision was not challenged in Alexandria until four years after it became law. In the summer of 1958, fourteen African American students in Alexandria sought transfers to white schools. Two days before the Alexandria desegregation trial was due to begin in October 1958, the School Board enacted a resolution that announced six criteria on which to evaluate transfers. Although none of these were based on race, they collectively allowed the Board to deny all 14 applicants.

In one case an African American girl performed above her peers at the white school but the Board said:

“This girl, if admitted to the sixth grade of either Patrick Henry or William Ramsay School will be the only pupil of her race if enrolled. This will be a novel situation. Such a situation will constitute a disruption of established social and psychological relationships between pupils in our schools as they have previously operated.”

The federal District Court ruled that, using the Board’s own criteria, nine of the students must be admitted to three all-white schools. On February 10, 1959 we have this iconic picture in the newspapers of the students making history.

In June 1959 the City Council voted to remove Herman G. Moeller from the School Board. He had been the only Board member to vote to desegregate the schools. The School Board continued to resist the transfer of African American students to all-white schools as far as it possibly could. This was a policy of containment.

1965: The Making of T.C. Williams High School

In January 1963, Superintendent T.C. Williams retired and the Board appointed John Albohm. Albohm announced a plan to fully desegregate within five weeks of starting with ACPS, moving 63 students immediately to different schools. The Board then put forward multiple motions to get him fired. Albohm was implementing changes even before the Civil Rights Act was in place, and it nearly cost him his job.

Albohm also had to find compromises to make desegregation work. He introduced the honors programs, primarily to stop white flight. He tackled concerns that his efforts to address the needs of African American students were taking away from other groups. He also started to address the needs of children in poverty so that they could succeed if they were transferred to an integrated school.

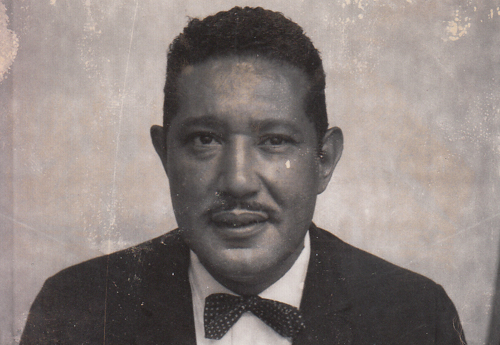

Alexandria’s middle-class African American population seized the moment and began to insist on better housing, education conditions and a political voice. In the summer of 1964, Ferdinand T. Day, who had been a key member of the Secret Seven, a group fighting for civil rights in Alexandria, was appointed to the School Board when it expanded from six to nine members. He later became the first African American to be elected chair of a public school board in Virginia.

Ferdinand T. Day

In 1969, violence erupted when a fourteen-year old student was beaten by a white police officer, in scenes that are still recognizable today. Two days later a group of African Americans marched to City Council demanding the officer’s dismissal. Alexandria was bombed nightly with 18 firebombs and a Molotov cocktail. In May 1970, just eight months after the police beating and two weeks before a city council election, an African American high school junior named Robin Gibson walked into a 7-Eleven on the corner of Commonwealth and West Glebe and was shot by the white store manager. Six consecutive nights of rioting and firebombing followed. More than 1,500 people attended Gibson’s funeral. The store manager was tried by a white judge and jury and served just six months behind bars. With Election Day just two days after Gibson’s funeral, black voter turnout doubled and Alexandria elected its first African American City Council member, Ira Robinson.

The turmoil was played out in schools with racial tensions spilling into classrooms and the gymnasium. Many parents perceived the continuation of past school policies as simply an effort to maintain racial hierarchies. In November 1970 a group of 20 white youth burned a cross in front of George Washington High School, a school that was 25% African American. Bathrooms were taken over, tarred and set on fire, and there were violent conflicts between students. Superintendent Albohm tried to talk to students but was told, “I’m tired of being told to go to my room.”

Albohm was required by the federal government to demonstrate the integration of four grades to continue to receive funding. While the elementary schools were most segregated at the time, he opted to unify the high schools, partly to help ease the racial tension. He hoped that this would ease concerns about African Americans being relegated to declining schools.

In what was dubbed the 6-2-2-2 plan, T.C. Williams High School would be built to serve all students in the city in grades 11 and 12. While Albohm could not immediately offer the African American principals and leadership they wanted, he could offer a chance to create a new school and climate. It was an attempt to anchor the experiences of all Alexandrians in one common place.