This year marks the 65th anniversary of the landmark Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education, in which the court unanimously ruled that racial segregation of children in public schools was unconstitutional.

Although Alexandria neither led the charge to resist desegregation nor was the first to desegregate in Virginia, in many ways the story of the initial steps to desegregate has come to represent the intensity of the issues and the racial conflict that persisted long after desegregation.

Many of us know the story of Remember the Titans. But the story of the desegregation of Alexandria City Public Schools is far more intense and darker than the glamorized and sanitized story presented by Disney. While ACPS and our community celebrate our diversity today, it took federal legislation, political unrest, violent protests, and changes in the composition of Alexandria’s School Board and City Council and a new superintendent to get to what at least looked like full integration — and even then it was not fully integrated in practice. It would be twenty years after Brown v. Board of Education before a full integration plan was in place in Alexandria and even now some of the issues the city faced at that time are still relevant today.

This article is the first in a series that explores the impact of Brown v. Board of Education on our schools and community, highlighting important milestones and key figures who played a role in the desegregation of Alexandria’s schools.

The entrenched nature of the Old Guard in both the city and the schools meant that the federal court decision ordering Alexandria City Public Schools to comply with Brown v. Board of Education in 1954 was a direct challenge to the local political situation. Alexandria’s mayor from 1952 to 1955 was Marshall J. Beverly, a cousin of U.S. Senator Harry F. Byrd, Sr. who led the statewide pro-segregation campaign known as Massive Resistance, while Alexandria State Delegate James M. Thomson was Bird’s brother-in-law. Alongside them was Superintendent Thomas Chambliss (T.C.) Williams and a conservative School Board. The affiliation was so strong that when the city eventually complied with desegregation it brought down the local regime.

Across Virginia, schools that desegregated voluntarily were closed down. In Alexandria, local officials strategically used these threats of state-imposed punishment and closure to argue for an indefinite delay of desegregation in the wake of Brown v. Board of Education. The court decision was not challenged in Alexandria until four years after it became law. In the summer of 1958 fourteen African-American students in Alexandria sought transfers to white schools. Two days before the Alexandria desegregation trial was due to begin in October 1958, the School Board enacted a resolution that announced six criteria on which to evaluate transfers. Although none of these were based on race, they collectively allowed the Board to deny all 14 applicants.

In one case an African-American girl performed above her peers at the white school but the Board said:

This girl, if admitted to the sixth grade of either Patrick Henry or William Ramsay School will be the only pupil of her race if enrolled. This will be a novel situation. Such a situation will constitute a disruption of established social and psychological relationships between pupils in our schools as they have previously operated.”

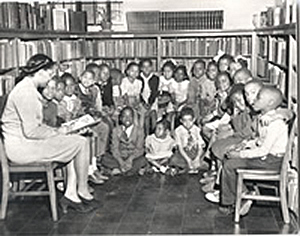

The federal District Court ruled that, using the Board’s own criteria, nine of the students must be admitted to three all-white schools. On February 10, 1959 we have this iconic picture in the newspapers of the students making history.

In June 1959 the City Council voted to remove Herman G. Moeller from the School Board. He had been the only Board member to vote to desegregate the schools. The school Board continued to resist the transfer of African-American students to all-white schools as far as it possibly could. This was a policy of containment.

So what changed?

In January 1963, Superintendent T.C. Williams retired and the Board appointed John Albohm. But it wasn’t smooth sailing. Albohm announced a plan to fully desegregate within five weeks of starting with ACPS, moving 63 students immediately to different schools. The Board then put forward multiple motions to get him fired. Albohm was implementing changes even before the Civil Rights Act was in place but it nearly cost him his job.

Albohm also had to find compromises to make desegregation work. He introduced the honors programs, primarily to stop white flight. He tackled concerns that his efforts to address the needs of African-American students were taking away from other groups. He also started to address the needs of children in poverty so that they could succeed if they were transferred to an integrated school. These were new and challenging concepts at the time but have had a lasting impact on the way we operate as a division.

Desegregation split the elites though and peeled off a group of more liberal thinking conservative Democrats. Alexandria’s middle-class African-American population seized the moment and began to insist on better housing, education conditions and a political voice. In the summer of 1964, Ferdinand T. Day was appointed to the School Board when it expanded from six to nine members. He later became the first African-American to be elected chair of a public school board in Virginia.

According to Doug Reed, a professor at Georgetown University, whose book, Building the Federal Schoolhouse this post is based upon:

The turmoil of American society was worked out in America’s classrooms with many white families confronting poverty and racial conflict within ‘their’ classrooms for the first time.”

T.C. Williams High School came out of this turmoil, which surprisingly can seem to have parallels to some of today’s national events.

In 1969, a fourteen-year old student was beaten by a white police officer. Two days later a group of African-Americans marched to City Council demanding the officer’s dismissal. Alexandria was bombed nightly with 18 firebombs and a Molotov cocktail. In May 1970, just eight months after the police beating and two weeks before a city council election, an African-American high school junior named Robin Gibson walked into a 7-Eleven on the corner of Commonwealth and West Glebe and was shot by the white store manager. Six consecutive nights of rioting and firebombing followed. More than 1,500 people attended Gibson’s funeral, while the store manager was tried by a white judge and jury and served just six months behind bars. With Election Day just two days after Gibson’s funeral, black voter turnout doubled and Alexandria elected its first African-American City Council member, Ira Robinson.

The turmoil was played out in schools with racial tensions spilling into classrooms and the gymnasium. Many parents perceived the continuation of past school policies as simply an effort to maintain racial hierarchies. This was played out with disputes over discipline and school quality. In November 1970 a group of 20 white youth burned a cross in front of George Washington High School, a school that was 25 percent African-American. Bathrooms were taken over, tarred and set on fire, and there were violent conflicts between students. Superintendent Albohm tried to talk to students but was told, “I’m tired of being told to go to my room.”

Albohm was required by the federal government to demonstrate the integration of four grades to continue to receive funding. While the elementary schools were most segregated at the time, he opted to unify the high schools, partly to help ease the racial tension. He hoped that this would ease concerns about African-Americans being relegated to declining schools. In what was dubbed the 6-2-2-2 plan, T.C. Williams High School would be built to serve all students in the city in grades 11 and 12. While Albohm could not immediately offer the African-American principals and leadership they wanted, he could offer a chance to create a new school and climate. It was an attempt to anchor the experiences of all Alexandrians in one common place.

The history depicted in this post is derived in great measure from “Building the Federal School House: Localism and the American Education State,” by Douglas Reed. The book goes into extensive detail about the evolution of the governance of public schools as local, state and federal bodies reconstructed the operation of schools in the U.S. using the City of Alexandria as a case study.

Learn more about the history of ACPS.